|

Review: Gray's AnatomyBy Dan KrovichNovember 24, 2002

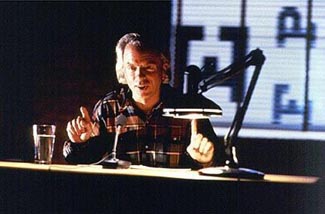

When making a film of a monologue performance, obviously the most important element is the monologue itself. If that basis is not entertaining, there isn't much a filmmaker can do to make it work. That doesn't mean that the filmmaker doesn't have an important role in a monologue film, however, because when making the transition from a live performance to a film, the all-important immediacy of interaction between performer and audience is lost. Just setting up a camera and hitting record is going to result in an inadequate translation at best, so it is up to the filmmaker to find a way to make the film visually interesting without losing the essence of the performance. In Gray's Anatomy, the first necessity is covered thoroughly, as Spalding Gray is one of the best and probably most famous monologue artists working today. Gray's Anatomy is the third film version of one of his monologues, following Swimming to Cambodia and Monster in a Box. As usual, it is a first person account, this time of Gray's experiences when he is diagnosed with a rare eye condition. Being told that surgery is the only cure for the condition, Gray sets out to find alternatives. That search leads him to try Christian Scientist faith healing, dietary methods, a Native American sweat lodge, and even a "psychic surgeon" in the Philippines. Soderbergh hearkens back to his own Yes concert film for inspiration, beginning the film with an archival educational film about the eye. He then segues into interviews with individuals who tell their own eye horror stories that will make anyone with an eye hang-up squeamish, before moving on to Gray's monologue. That monologue, in addition to being an amusing account of a slightly neurotic, doctor-phobic individual's account of how he dealt with a medical condition, also informs about how different cultures address disease, health, and healing. Visually, Soderbergh takes a fairly literal approach to the monologue, using backgrounds and props that reflect Gray's words. For instance, the use of eye examination props early in the film and of shadows acting out the action in the background lateron give the viewer a visual suggestion without explicitly spelling out every detail. The mixture of these suggestive images with Gray's descriptive words guides one to imagine a stylized, but not quite literal, perception of events. Soderbergh also judiciously interrupts Gray by occasionally cutting back to those interviewed about their own eye injuries at the start of the film to get their reactions to how Gray has gone about handling his own. This fairly simple device helps provide other points of view, and gives the audience a brief break from Gray. It's a small thing, but even though Gray is entertaining, listening to one person talk for eighty minutes straight can be a challenge. These short breaks allow you to take a quick breath before heading back in to the next story. Gray's Anatomy represents the collaboration between two of the most talented men in their respective fields. They apparently worked together extremely well, so their contributions and style blend without one overpowering the other. The words and visuals combine to form a fascinating and entertaining journey through the eyes of a master of the monologue. |

Wednesday, February 05, 2025

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.