|

Wladislaw Starewicz: Animation PioneerSeptember 13, 2002

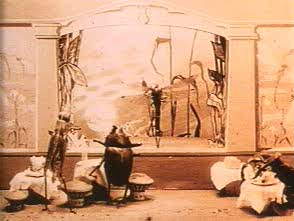

Twenty-first century cinema audiences are so jaded that few genres can still instill the kind of innocent wonder that must have greeted the audiences in the early nickelodeons. Animated film is an exception to this, however, as advances in this area have brought about a renaissance in this long-lived film form that allows it to maintain its power. And yet still we have forgotten many of the seminal giants on whose shoulders today's geniuses stand. The historic cartoon work of Disney and Warner Bros. certainly doesn't suffer from this problem, since the existence of these companies as worldwide entertainment giants makes their greatest work widely available for viewing. Less well known are important forefathers such as Emile Cole, Winsor McCay, John Randolph Bray and Otto Mesmer, as well as the man who more or less invented stop-motion animation: Wladyslaw Starewicz. Born in Poland sometime in the late 1800s (dates of both 1882 and 1890 are given in the literature), there are varying accounts of the director's early life. What is certain is that he went to the Academy of Fine Arts in St Petersburg, Russia in the early 1900s to study, and from there somehow entered into his work as an animator. A former producer (Alexander Khanzhonkov) claimed to have discovered him after the costumes he designed for a Polish Christmas pageant were written up in the press, yet Starewicz himself is known to have said that his career began when he decided to make some short entomological documentaries while director of a Lithuanian natural history museum. It really matters little which of these stories are true, however, for what is important is that sometime after 1910, this man began to make a kind of movie that had never previously been seen before. Utilizing his interest in the insect world, this young director began to make movies that starred the denizens of nature acting in Aesopian-style moral fables. Building on the stop-the-camera ideas of fantasists like Melies and wedding them with a sort of frame-by-frame exoskeleton puppetry that gave the illusion of motion, Starewicz hit on a style of animation whose legacy would later be seen in works such as The Nightmare Before Christmas and Chicken Run. This early Russian work consists of a series of short films that are just as engaging and technically impressive today as they must have been at that time, chief among them being the brilliant and hilarious The Cameraman's Revenge, truly one of the great masterpieces of early animated film. The plot of this melodramatic short piece revolves around Mr and Mrs Beetle and the romantic complications of their fractious relationship. Both of the beetles are dissatisfied with their humdrum lives and take it upon themselves to escape their ennui with adultery. Mrs Beetle takes up with a beret-wearing cricket, while Mr Beetle himself fools around with a sultry dragonfly. However, the dragonfly's boyfriend happens to be a cameraman who voyeuristically films the infidelities of Mr Beetle through a hotel room keyhole so that he might later extract his pound of flesh. After returning home and finding his wife amorously involved with the artist on the couch and then throwing a hypocritical fit, the Beetles head out to the cinema, whereupon the cameraman grasshopper projects the illicit footage of the husband's cheating on the screen, much to the delight of the various bugs in attendance. Mrs Beetle then chucks her hubby through the screen; the ensuing fight causes the projector to catch fire and the two are then reunited for life, though the ending implies that their wedded "bliss" will continue from behind the bars of a jail cell. While the wry implications of Starewicz' humorous tale have their part in the success of this little gem, it is impossible to ignore the impact of its technical achievement as well. The director uses naturalistic lighting and real-world scale to emphasize the setting, and the animation is so painstakingly well done that you simply accept the story as it plays along, rather than noticing any limitations in its facilities. For this to still be true of a film made nearly a century ago is a testament to the genius behind it; the short has a timeless quality that makes it still seem fresh today, something that cannot be said of most of the live-action films from that same time period. After making eight animated films in his early career, the First World War interrupted Starewicz' work and he spent some time making live-action features. Then, shortly after the Russian Revolution, the director left the country to settle in France and return to his work as an animator. For the rest of his life he would devote himself to making independent stop-motion puppetry films, mostly featuring animals engaged in children's stories with intelligent moralistic shadings. His later work is somewhat softer and less zoological than those first movies that tend to use escapees from the entomology cabinet, yet it expands the technical facility of those initial films to feature length and achieves greater emotional depth with this growth. A prime example is 1930's Tale of the Fox, a version of a story by Goethe that stands as another masterwork by this now forgotten talent. This 65-minute tour-de-force is now sadly out of print, though it would seem to be well deserving of a DVD release, both for its complex ethic narrative and the incredible quality of its animation. It is unfortunate that this great film is as yet unreleased on DVD, but animation fans that are interested in this Polish animator's films can look for older video versions and may also wish to seek out the excellent Milestone Collection that contains The Cameraman's Revenge and five other of the director's short features. Viewing these films today, what is most striking is how well they hold up, as the thorough ease of the animation maintains its ability to awe even if it seems somewhat quaint in style to eyes used to the wonders of a Toy Story world. Also edifying is Starewicz' innate ability to tell his stories intelligently without the preachy patronizing often prevalent in current mainstream work. But what's most impressive is viewing this groundbreaking work in the context of some of the excellent animation that has been made within the last 20 years; people like the Brothers Quay, Jan Svankmajer and Nick Park owe Starewicz a great debt, as do many other animators and special effects personnel who use the stop-motion technique. It seems almost inevitable that this mode of animating films would have eventually been developed for the medium, yet by maintaining such an exceptionally high initial overall standard with his films, this great, though now neglected, filmmaker made the style both instantly appealing and lastingly entertaining. Film audiences of today should pay tribute to this pioneer by rediscovering his early films, and discovering for themselves the foundations upon which today's animated blockbusters are built. References: Crafton, Donald. Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 1984.

|

Saturday, December 13, 2025

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.