|

|

Visionaries and Their Visions: Orson WellesBy Alex HudsonMarch 10, 2004

At 23, he conquered radio. At 25, Orson Welles conquered cinema.

RosebudOutside, the boy plays in the snow. Inside, his mother signs his life away.Deep focus allows us to simultaneously see mother in the foreground and boy in the background through a window. Unaware of his fate, young Charles Foster Kane enjoys what are possibly his final moments of true bliss. Nineteen minutes into his first film, Orson Welles has crafted a scene as technologically advanced as it is emotionally wrenching. Citizen Kane pushed the bounds of cinema further than any film before or since. While deep focus and nonlinear storytelling had been done, they had never been done with such groundbreaking precision.

Kid from KenoshaBefore Kane, there was Kenosha. Precociousness incarnate, extraordinary Orson was born in ordinary Kenosha, Wisconsin. Like semi-autobiographical Charles Foster Kane, Orson lost his family, and by extension his innocence, early. Orson's mother, Beatrice, died when he was nine and his father, Richard, died six years later.Orson found salvation as well as father figure at the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois. Headmaster Roger Hill, impressed by his fascinating newcomer, took Orson under his wing; instilling in his protégé a love of Shakespeare, performing and all things theater.

Ambitious EgoSomewhere in the life of a director there's a time period that decides their fate; a time, whether they know it or not, that sets them irreversibly on the road toward filmmaking. For Orson, it was his stay at Todd School. Ever the quick study, Orson wrote, directed and starred in school theatricals. Ambitious and dramatic with a healthy ego to boot, young Welles proved a natural performer.Orson parlayed his ambition into real world theatrical success almost from the start. After graduating from Todd, he traveled to Ireland where he honed his craft at Dublin's experimental Gate Theater. A year later, he returned to America and soon made his Broadway debut, at 18, in Romeo and Juliet. Kismet called when Orson met director/producer John Houseman, whom he befriended, and together the two formed their own repertory company, The Mercury Theater. During the next three years, Orson Welles would conquer Broadway, the airwaves and Hollywood. The Mercury Theater's production of Julius Caesar took Broadway by storm. Welles' twist: transfer Shakespeare's Rome to Mussolini's capital. The modern dress play won rave reviews, drew capacity crowds and eventually toured. Empowered by his success, Welles branched out to radio, making good use of his distinctive baritone. On Halloween Eve 1938 Welles panicked a nation with his broadcast of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds. Delivered as breaking news, the story of Martian invasion so utterly convinced listeners, thousands fled their homes in horror. Hoping to capitalize on Welles' notoriety not to mention his prodigious talents, RKO Pictures offered Welles unprecedented freedom to write, direct and act in two films of his choosing. Welles came to Hollywood intent on filming Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness but abandoned the seminal yet unfilmable story to make Citizen Kane.

Pathos of TwilightOn his very first try Welles proved his artistic might and changed the course of film history. Yet the shadow cast by Citizen Kane obscured the genius of Welles' subsequent films.Pressured to surpass the unsurpassable, Welles nearly achieved the impossible with his adaptation of Booth Tarkington's The Magnificent Ambersons. Drawn again to a story about disintegration of family, Welles saw parallels to his own life in Tarkington's novel of a fin-de-siècle family struggling to adapt to the machine age. A meditation on aging, The Magnificent Ambersons chronicles the end of 19th century innocence and the coming of 20th century bustle. Lushly photographed with impeccable production value, Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons was set to rival, if not eclipse, Kane. However, deep into editing the film, Welles was asked by the US State Department to shoot a goodwill documentary in Brazil meant to solidify US-Latin American relations. Welles obliged, leaving RKO exact instructions how to finish Ambersons. But RKO flinched. They test screened Ambersons on a Saturday night after another test screening of the upbeat musical The Fleet's In. Predictably, the mostly teenage audience despised the dour Ambersons, laughing at inappropriate times. RKO promptly sliced out 50 minutes from the film, burned the cut footage and re-shot a new "happy" ending. Welles' Mona Lisa was defaced. A cinematic butchery without equal, the episode derailed Welles' locomotive of success precisely as it was gathering full steam.

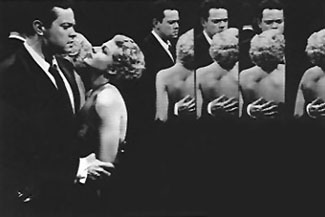

Playing With ShadowsThe Wellesian aesthetic is essentially rooted in noir. With their sumptuous shadows, artful camera angles and intricate compositions, Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons codified the visual language of film noir. And while both films transcend genre, their overall visual complexity established the framework for the noir picture.The Lady From Shanghai, starring the second Mrs. Welles, Rita Hayworth, provided Orson with yet another dalliance into the darkest of genres. The Lady From Shanghai weaves a tangled web climaxing in a bravado finish. More than anything, Welles understood the importance of climactic endings. From the revelation of rosebud in Citizen Kane to the shoot-out in the fun house in The Lady from Shanghai, Welles' films end memorably.

Filming ShakespeareAn ultimate test of a director is whether he can translate Shakespeare to celluloid. Enamored with the bard from his days at Todd School, Welles gravitated first to Macbeth, casting himself in the eponymic role.Like Akira Kurosawa, Welles instinctively realized the key to filming Shakespeare rests largely in the creation of setting. For Macbeth, Welles imagines a fog shrouded wasteland with witches hovering atop cauldrons. Overly theatrical, Macbeth functions mostly as warm-up for Welles' second cinematic stab at Shakespeare, Othello. Gloriously atmospheric, Welles' Othello is a visually transcendent example of pure cinema. Funding for Othello disappeared before production began in Morocco. Undeterred, Welles defiantly spent the next three years making the film himself, acting in films like The Third Man and The Black Rose to finance the project. Famously, the costumes never arrived at one Moroccan location so Welles improvised by shooting the scene in a Turkish bath, with the actors in towels. Returning to Shakespeare, Welles helmed Chimes at Midnight, a skillful merging of several plays featuring the comically rotund and rotundly comic Sir John Falstaff. Again Welles played the lead and again Welles took ownership of Shakespeare. Mature, almost serene, Chimes at Midnight boasts a sublimely masterful battle sequence, The Battle of Shrewsbury, that rivals the swordplay in Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky and Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai.

All or NothingInstead of conforming to the mediocrity and churning out sleek Hollywood product, Welles exiled himself to Europe where he was destined to make films like Chimes at Midnight on small budgets with enormous heart. Each Welles film inherently became a labor of love. Each film became a crusade to appease his artistic conscience. Films like Othello, Chimes at Midnight and The Trial, based on Franz Kafka's absurdist novel, testify to Welles' uncompromising artistry as a filmmaker. They represent the fruition of Welles' all or nothing gambit while unfinished projects like Don Quixote and The Other Side of the Wind represent the tragic downside.Welles made art films before art films existed. He was a one man revolution, a harbinger of the sea change that would empower the artisans. Studio bosses shunned Welles, knowing he symbolized their irrelevance. In his last 27 years, Welles directed one film in Hollywood. Ironically, he wasn't originally slated to direct Touch of Evil, he was merely to act in the B-movie. But Charlton Heston joined the production under the assumption Welles would also be directing. Producer Albert Zugsmith, upon realizing the situation, hired Welles to direct to placate his star. Touch of Evil pushes the Wellesian universe to its grotesque limits. Bloated and seething, Welles' Captain Hank Quinlan is large in every sense. From his portrayal of Charles Kane onward, Welles always played characters bigger and older than himself. Welles equated physical stature and age with importance; literally the bigger the man, it seemed to Welles, the greater his importance. As poignant as film gets, Touch of Evil is a fitting swan song, both to Welles' career in Hollywood and to the classic noir period that Welles helped launch. Welles' Captain Quinlan, exhausted from years of self-love, goes head to head with Heston's Mexican officer Mike Vargas. Vargas catches Quinlan framing a murder suspect and the two spend the rest of the film wrestling for control. Corrupt and racist, Quinlan still manages to hold our sympathy; he's a tragic figure embodying, in many ways, the pent-up frustration of Welles' failures. There's a piece of Welles in all his characters: Charles Kane is the birth of his own legend whereas Hank Quinlan is the smoldering ruin of that legend. Touch of Evil is Welles' Hollywood epitaph, carved in sweaty, embittered strokes.

Director as ArtistBy age 25, Orson Welles had conquered every medium of the day. His was true genius. The kind that makes artists.When Welles came to Hollywood, directors were technicians paid to oversee films. Besides rare exceptions, directors were overseers. Welles obliterated this concept. Writing, directing, acting, producing and even funding some of his films, Welles liberated film from the studios.

Ultimately, Welles' ego was the real star of his films. His insatiable ego compelled him to make cinematic monuments to himself, to prove his greatness by doing things in cinema never before done. Hitchcock was a genre onto himself. Welles transcended genre. Orson Welles was bigger than anyone. He was bigger than life.

|

|

|

|

|

Sunday, December 14, 2025

© 2025 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.